The 7 Carl Barks comics DuckTales fans need to read

By Christopher Gates Posted in Comics on August 11, 2017 10 min read

Can’t wait for the next episode of Disney XD’s DuckTales? We have some good news. If you need a quick fix of your web-footed friends, there are literally hundreds of comics out there starring the DuckTales gang, all written and drawn by a cartoonist named Carl Barks.

In fact, without Carl Barks, there would be no DuckTales. In the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s, while working on Disney’s comic book line, Barks created Uncle Scrooge, Duckburg, the Beagle Boys, Magika de Spell, Scrooge’s money bin, the Junior Woodchucks, and pretty much everything else that makes DuckTales, well, DuckTales. Barks transformed Donald Duck from Mickey Mouse’s irritable sidekick into an adventure hero. He made Huey, Dewey, and Louie into stars, and introduced characters like Flintheart Glomgold and Gyro Gearloose into Disney canon.

There’s just one problem: during his tenure as “the good duck artist,” Carl Barks wrote and drew over 600 comics. It’s hard to know where to start. That’s why we asked a panel of experts—professor Daniel Yezbick, author Peter Schilling, and Carl Barks Fan Club President Ed Bergen—for help. No matter what kind of DuckTales fan you are, there’s a Barks story out there for you. We’ll help you find it.

For the romantic: “Back to the Klondike”

Carl Barks’ stories provide DuckTales’ foundation, but as any fan will tell you, the comics and the cartoon aren’t quite the same. Both series focus on wild adventures and globe-trotting treasure hunts, but Barks plays social satire in his stories, and doesn’t hesitate to take absurd digressions. By comparison, DuckTales is more straightforward.

Daniel Yezbick, a regular contributor to Fantagraphics’ The Complete Carl Barks Library and author of Perfect Nonsense, urges DuckTales fans to check out “Back to the Klondike,” which is available in the Only a Poor Old Man collection. In “Back to the Klondike,” Scrooge McDuck takes some pills to bolster his failing memory and suddenly remembers that he owns a gold clam in Alaska. That’s also where he met the beautiful, wily, and resourceful saloon singer Glittering Goldie, who he might have feelings for. Maybe.

After many shenanigans (including bar brawl that’s so brutal that Disney censored it during “Back to the Klondike’s” first printing), Scrooge and Goldie reunite, and Scrooge proves that he has a heart of—well, not gold, exactly. More like copper. “Back to the Klondike” is a surprisingly heartfelt story, and proves that Scrooge, who can come sometimes feel a little one-note, has a lot of depth. You just have to dig deep to find it.

Oh, also? “Back to the Klondike” is, like DuckTales, both exciting and riotously funny. Yeznick says that “Back to the Klondike” epitomizes the “infectious sense of wonder” that drives all of the “excitement, discovery, and exploration” that attracts people to both Barks and DuckTales. In fact, “Back to the Klondike” fits the DuckTales formula so well that in the ’80s DuckTales producers adapted it into an episode called, appropriately enough, “Back to the Klondike.” If the story seems familiar, that’s probably why.

For the raider of the lost ark: “The Golden Fleecing” and “The Fabulous Philosopher’s Stone”

DuckTales isn’t the only Disney franchise that owes a lot to Carl Barks. Indiana Jones does, too. Steven Spielberg lifted the rolling boulder scene that kicks off the Indiana Jones franchise from Barks’ “The Seven Cities of Gold.” Dr. Jones’ co-creator, George Lucas, admits that Uncle Scrooge’s “ingenuity, integrity, determination, a kind of benign avarice, boldness, a love of adventure, and… sense of humor” directly informed Indiana’s character.

DuckTales isn’t the only Disney franchise that owes a lot to Carl Barks. Indiana Jones does, too. Steven Spielberg lifted the rolling boulder scene that kicks off the Indiana Jones franchise from Barks’ “The Seven Cities of Gold.” Dr. Jones’ co-creator, George Lucas, admits that Uncle Scrooge’s “ingenuity, integrity, determination, a kind of benign avarice, boldness, a love of adventure, and… sense of humor” directly informed Indiana’s character.

You can see all of this at play in “The Golden Fleecing,” which Yeznick calls “a hilarious riff on Jason and the Argonauts, complete with ferocious dragons, secret missions, and atrociously strange ’50s gender and ethnic stereotyping that typifies a lot of Barks’ satire.” Carl Barks Fan Club president Ed Bergen lists “The Fabulous Philosopher’s Stone,” in which “Scrooge is on the hunt for the ‘stone that turns all metals gold’ which… after many twists and turns, actually turns its owner into gold,” as a personal favorite.

It’s easy to see why. In both of these stories, Scrooge recruits Donald and his nephews as helpers and takes off to search for artifacts from Greek mythology. Naturally, neither journey goes according to plan, and it’s not long before Scrooge and company find themselves up fighting the same monsters as the ancient Greeks. If you’re looking for a good example of Barks’ adventure stories, you can’t do much better than these (conveniently, both stories are available in Fantagraphics’ The Seven Cities of Gold compilation).

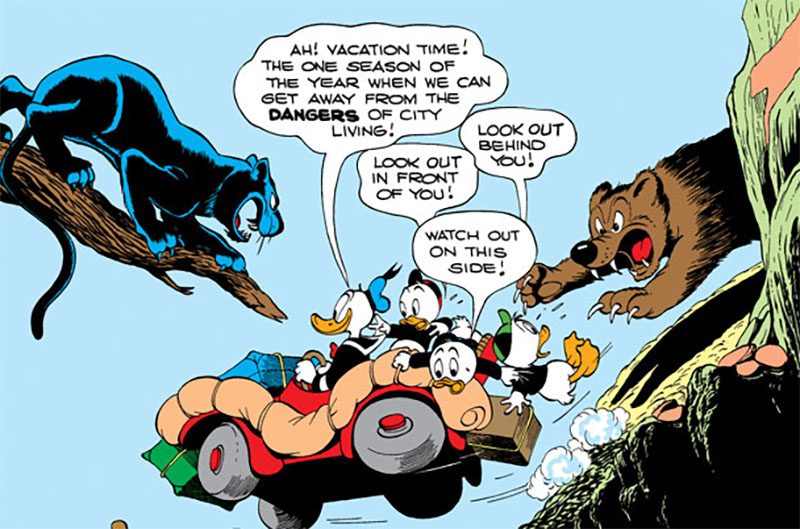

For the environmentalist: “Vacation Time”

Donald Duck barely appeared in the first DuckTales cartoon (allegedly, Donald’s raspy voice made him too difficult to understand on television), but he plays a major role in the new series, and he’s a main character in Carl Barks’ stories, too. In fact, Carl Barks’ Duck author Peter Schilling prefers Donald to Scrooge. As Schilling explains, “[Donald’s] stories can be about anything, whereas Scrooge’s money is the focus of every story.”

Donald Duck barely appeared in the first DuckTales cartoon (allegedly, Donald’s raspy voice made him too difficult to understand on television), but he plays a major role in the new series, and he’s a main character in Carl Barks’ stories, too. In fact, Carl Barks’ Duck author Peter Schilling prefers Donald to Scrooge. As Schilling explains, “[Donald’s] stories can be about anything, whereas Scrooge’s money is the focus of every story.”

“Vacation Time” might be Donald’s shining moment. Unlike Scrooge-driven adventures, “Vacation Time” has no treasures. There are no monsters. Donald simply takes Huey, Dewey, and Louie camping in the woods. That’s it.

Of course, with Donald at the helm, nothing goes smoothly. Schilling compares “Vacation Time’s” Donald to The General’s Buster Keaton, a “guy [who] goes headfirst into an adventure (Donald wants to camp and get a prize-winning picture of a deer),” but reveals “very subtly that he has some skills buried beneath his incompetence.”

Despite his bluster, Donald proves in “Vacation Time” that he’s a capable and thoughtful outdoorsman, and when a fellow camper starts a deadly forest fire (as Yeznick notes, both Barks and his wife were fervent conservationists), Donald steps up and saves the day. “Often in these tales, the kids bail out Donald,” Schilling says. “But here, Donald is the leader, the adult, without whom the kids would literally die. It’s a great, great adventure.”

For the classic film buff: “The Golden Helmet”

To Schilling, Donald is a like an old Hollywood actor. His personality remains constant from story to story, but his circumstances constantly change. In that way, he reminds Schilling of Golden Age Hollywood star Cary Grant. “Grant didn’t have a tremendous range,” Schilling says. “You went to see one of his movies to see how fun it would be to watch Cary Grant be a scientist, newspaper editor, union hell-raiser, [or] whatever.”

To Schilling, Donald is a like an old Hollywood actor. His personality remains constant from story to story, but his circumstances constantly change. In that way, he reminds Schilling of Golden Age Hollywood star Cary Grant. “Grant didn’t have a tremendous range,” Schilling says. “You went to see one of his movies to see how fun it would be to watch Cary Grant be a scientist, newspaper editor, union hell-raiser, [or] whatever.”

“The Golden Helmet,” in which Donald finds a treasure map hidden in an old viking ship, shows off Donald’s full potential. The story has all of the hallmarks of Uncle Scrooge and DuckTales’ treasure-driven adventures—”Barks loved to draw seascapes, and this one has tremendous water voyages,” Schilling observes—but with Donald in the lead role, the dynamic changes. In “The Golden Helmet,” Donald serves as a security guard, a sailor, a treasure hunter, an outdoorsman, a would-be king, and a reluctant hero. With every role, Donald shows a new side, and he emerges from the story as a fully-rounded character.

It’s a funny, dramatic story, too. See, whoever finds vikings’ long-lost gold helmet will be crowned king of North America, and will be able to rule the continent as he sees fit. A madcap, slapstick dash around the world follows, as Donald races the villainous Azure Blue to the prize. Things take a darker turn, however, once Donald retrieves the helmet and discovers that its power is hard to ignore. Just like Donald, “The Golden Helmet” lets Barks exhibit his full range as a storyteller. It’s an absolute must-read.

For the fan who, well, it’s complicated: “Luck of the North”

“Luck of the North,” which appears in Fantagraphics’ Trail of the Unicorn, is Ed Bergen’s pick for Carl Barks newcomers, and with good reason: it’s the one that got Bergen hooked as a kid, and remains one of his favorites to this day.

He has a pretty good guess why, too. In “Luck of the North,” Donald displays a wide range of emotions. As Bergen describes it, “Luck of the North” sees Donald experience “glee in sending his cousin, Gladstone, off on a wild-goose chase, remorse in considering what might happen to Gladstone at the North Pole, and then determination, with the nephews, on going to the North Pole himself to attempt to rescue Gladstone from any potential problem.”

By the end of “Luck in the North,” Donald emerges as a fully-fledged character, and one who’s much deeper than you’d expect given his cartoon roots. “Donald comes across to me as really human in that story,” Bergen says, “with all the attendant human emotions regarding any decisions we make and the morals or ethics involved in those decisions.” Bergen cites a quote from a friends’ Carl Barks exhibition to explain what he means: “Die Ente ist Mensch Geworden,” or “The Duck Has Become Human.” “That’s what I think really engaged me, and would engage others, and draw them to Carl’s work today,” Bergen says. “The stories are timeless!”

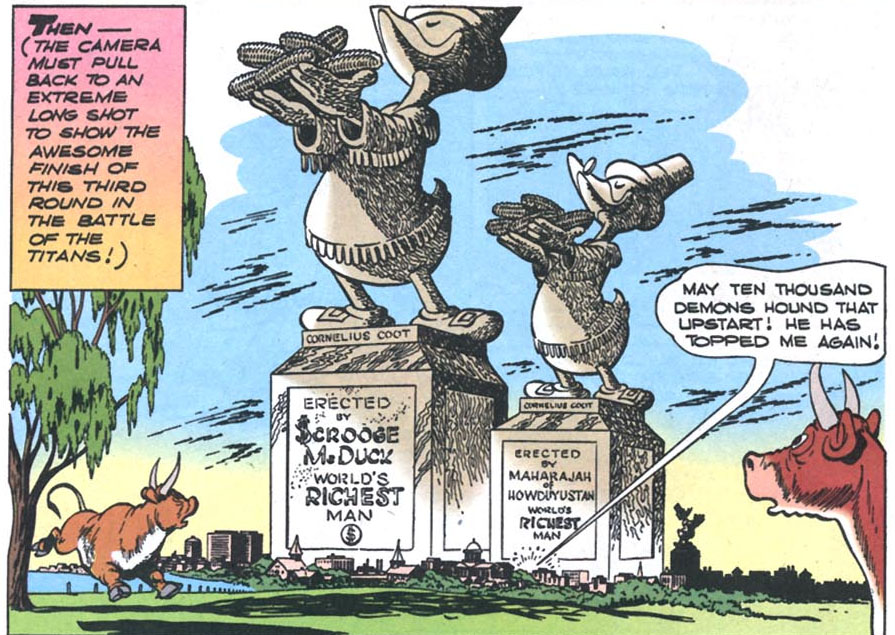

For the reader who’s short on time: “Statuesque Spendthrifts”

Speaking of time, while Carl Barks’ adventure stories get most of the attention, the artist produced a number of short 10-page comics as well. “Sometimes, these stories are underappreciated as they are not usually the broad, sweeping adventure tales,” Begen says, “but they deal with some of our regular human emotions and foibles that are common to us all in real life.”

In fact, one of Barks’ best stories, according to Bergen, is the 10-page comedy “Statuesque Spendthrifts.” In the comic, Scrooge and the Maharajah of Howduyustan (get it) face off to determine who’s the richest man (or duck) in the world. Over the course of the story, Scrooge and the Maharajah build a series of increasingly ludicrous statues of Duckburg’s founder, Cornelius Coot. At the end, the Maharajah is bankrupt, Duckburg is flooded in unwanted sculptures, and Scrooge… well, that’d be telling.

It’s a good story some of Barks’ best visual comedy, but “Statuesque Spendthrifts” serves another purpose, too. While Carl Barks’ adventure stories send Scrooge and Donald around the world, the shorts focus on life at home in Duckburg. If you want to know more about the city where most of DuckTales’ action takes place, Barks’ shorts will tell you everything you need to know—and hey, they’re pretty fun to read, too!

Everygeek is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites. Those Amazon links above? They let us pay our writers and maintain the site. So, y’know, go ahead and buy something!